Riding through history

There are three ancient passes connecting inner Anatolia to the East Mediterranean coast (ancient Lycaonia to Cilicia Pedias); Gulek, Sertavul and Dumbelek. Whereas Gulek and Sertavul passes have been transformed in to highways where hundreds of cars and trucks cross every day, whereas the Dumbelek pass has remained in the shadow of past. This pass is presently only used by the nomads migrating from lowlands to mid Taurus ranges or vice versa and by few villagers. Being an important pass connecting ancient Lycaonia to Cilicia we decided to cross the Dumbelek pass where adverse climatic conditions prevail. The history of the route we followed dates back 2000 years. There you come across small villages and nomads’ settlements (Yoruk obasi). The best season to take this route is between June to August. It is worth mentioning to take precautions against the harsh climatic conditions of this geography.

Nomadic Turkmens of west wing of Taurus mountains (Taurus proper) from Gulf of Antalya to the north of Adana call themselves Yoruk. They are nomads spending the winter in coastal lowlands and migrating to highlands of Taurus range in summer. Some Yoruk families still live in tents throughout the year, whereas some own a house in the lowlands where they dwell during winter. Our first camping site was Huyuk Alani (Huyuk-Hoyuk Alanı – Tumulus area in Turkish). Nomads spending their summer in Huyuk Alanıi are Yoruks of Huzurkent in the district of Tarsus, Mersin. About 15 families camp at this site at an altitude of 2400 m. Huyuk Alani with a mosque, cemetery and large plain is somewhat a meeting center compared to the other camping sites. Water is supplied from a well. There is an empty room where guests can stay. Electricity is supplied by solar panels and there isn’t any mobile line connection.

The cemetery, an old cemetery with graveyards hundreds of years old, was lastly used during 1970’s since then the corpses have been transported down to Huzurkent for burial.

Migration from coastal lowlands to highlands and vice versa takes four to five days. Trucks and tractors are used instead of camels and black tents woven with goat hair changed to tents covered in plastic sheets. Nowadays, nomads cover the permanent wooden poles with plastic sheets whereas some have built stone dwellings. They migrate at mid May to Huyuk Alani and stay there till the end of August. Growing population, houses and cultivated land around villages makes it hard to migrate for nomads with their herd from day to day. Such burdens force the nomads to settle down. The young nomads seek for better living conditions in towns and cities. We, probably witnessed the last Yoruks still practicing full nomadism.

Yoruks are very hospitable, you would never be left hungry and thirsty. There are no discrimination between men and women, all work is done together. When visiting the Yoruks, one must take care of proper dressing and behavior. Though the Yoruks are friendly and caressing they might be very tough at the same time. Paying attention to these issues you would enjoy your stay with Yoruk families. You will feel the warmth of the people you won’t encounter in the cities. But never trust to the distance description of the Yoruks. If you are told it is just a distance of “ote yuz – the other side of the hill” it would mean you have at least a couple of hours of travel. We learned this the hard way : )

Let us mention an interesting situation we got caught in. The first night while we were sitting in a tent of a Yoruk family, Hanifi asked “are you coban (shepherd in Turkish)?” The answer was a harsh NO, “we all are Yoruks.” Everybody was looking at Hanifi and we felt somewhat uncomfortable. (Sheepherding is a job which one is paid for, but being a Yoruk is a cultural matter. That was the cause of their harsh response). One of the stories we were told about the nomadic life was as such: One of the Yoruks became tired of migrating up and down and had decided to stay in high land for the winter season. He had stored all his equipment and provision in a cave. At the summer time the migrating Yoruks had found a letter on which was written: Not hunger, not thirst and not the cold has killed me but the boom of mountains, the sound of the wind and the fear of thunder killed me.

Following a Yoruk’s saying “tedarikli basa kar yagmaz – snow will not fall on sheltered head ” we got up early in the morning to put down our tents and prepare our breakfast. After breakfast we got some valuable information about our route from the Yoruks and set off. Our plan for today was to pass Dumbelek plateau and arrive in Berendi village of Karaman province a 35 km ride distance from Huyuk Alani on dirt road with up and downs and occasional stony path passages. Some part of the route, especially through dried river beds, was in bad condition due to melted snow.

Leaving Huyuk Alani we arrived in Ayipinari (Bear’s spring) after 200 m of climbing. There we met Emin and his younger brother. They are grazing their herd at this site for two years where four families live. Compared to Huyuk Alani this camping site is somewhat more protected from the harsh winds.

We were told that there are ruins of a church but when we arrived we saw only stones scattered all around. Treasure hunters had come to this place well before us. Our researches later have shown that our route over Dumbelek pass was following an antique route connecting inner Anatolia to the Mediterranean coast and the ruins belonged to a khan (caravanserai). Unfortunately, living on the remains of a huge civilization we barely protect those historical artifacts.

We met a Yoruk beside his herd after we left Ayipinari, the first thing he asked us was: “Do you need anything? Were you supplied with bread and chai (tea) at Ayipinari?” We answered yes and asked him whether he needs something and his reply was: “Do you have cigarettes?” Unfortunately, none of us were smoking. He told us it is hard for a smoker to run out of cigarettes in the middle of nowhere. The next time we rode though this route we had some cigarettes but couldn’t find him. : )

We arrived in Ulubel after a short but steep ride on dirt road. Here we were welcomed and offered Kilan borek (flat bread filled with butter and sheep cheese warmed up on wood stove). The two families in Ulubel were living in stone houses with earth covered roofs built by their ancestors. We were told that this site was named Ulubel (howling pass) due to the howling sound of strong winds.

We continued to ride on dirty road with up and down hills till Berendi village. Although there aren’t any trees and no water, this wild natural beauty attracted our attention. Ground squirrels endemic to Taurus mountains show up here and there. There are nomad’s tents scattered all around the route. Passing such Yoruk obas (oba – camping sites of nomads) we slow down since the shepherd dogs are really scary : )

Berendi is divided into five districts Yenikoy (new village), Akoluk (white gorge), Keşir (carrot in local language), Aşagi (lower) and Yukari (upper) Kiraman belonging to Karaman province. It is said that the name Berendi comes from “barindi” (housed in Turkish). People of Berendi are very hospitable and friendly. They entertain travelers coming to their village. Show suitable places to camp and call for chai in the evening. We were invited for lunch by one woman while the other brought over some food from her home. They make their income from agriculture and herd keeping. We were offered fruits from their gardens and allowed to pick as much as we wanted from the trees. Berendi has also a very tasty spring water. As in many small Anatolian villages migration to cities, mostly to Eregli, has unfortunately emptied Berendi.

The house of Hafiz Osman in the center of Berendi is worth to mention. At the wall of the house carvings of symbols of the Turkish flag, his name in Ottoman and the building date can be seen. In the interior of the house wooden door and cupboard ornaments made by Hafiz Osman can be seen. The historical old city and the narrow gorge behind are worth visiting. Let us mention a saying we heard from many people of Berendi:

Don’t be a guest in Divle

Don’t be a donkey in Kiraman

Don’t be a bride in Berendi…

(Used to say that people of Divle are not hospitable, in Kiraman donkeys are used for transportation and hard work waits for the brides in Berendi)

After Berendi we rode through Kiraman and then stopped in Ucharman village, former Divle to visit the obruk (natural sinkhole) where the famous Divle cheese is stored to ripen. The keeper of this obruk is usually to be found in the village cafe or at home just nearby. The obruk is about 50 m deep and an elevator is built in. Divle cheese is packed in goat skin and left to ripen in the moist and cold air prevailing in the obruk. This cheese costs 45-50 TL per kg. Divle cheese festival is held in Istanbul, since people mostly migrated to Istanbul.

After Divle we rode towards Andikara village. The moorland of Anatolia was now prevailing which we felt immediately by increasing temperatures. Our destination for today was Buyukkorash village passing through Andikara – Melikli – Kavakozu. From Buyukkorash to Tashkale it is possible to cycle through the canyon along the river. We camped just outside Buyukkorash in the canyon where we met Mesut a young shepherd 14 years old and his sister Alime (11) grazing sheep belonging to their family.

The route following the river in the canyon from Korash to Tashkale was pleasant. There were many fountains along this dirt road. On the road to Tashkale, there is a small village, Kizillaragaini (kizillar- red people, aga – landlord, in – small cave), with old stone houses worth to stop and stroll around. The legend of this village says:

In the times when Yoruks migrated with camels one of them had fallen in love with a girl from Tashkale. But the girl wasn’t a nomad and the Yoruk decided to settle down in this village. He prepared a field for himself surrounding with a stone wall. But, villagers got angry and destroyed his field. The Yoruk killed all the villagers, sold his herd and finally hided in a cave. The name of the village became Againi (cave of landlord). The word Kizillar (red people) comes from the Turkmen tribes.

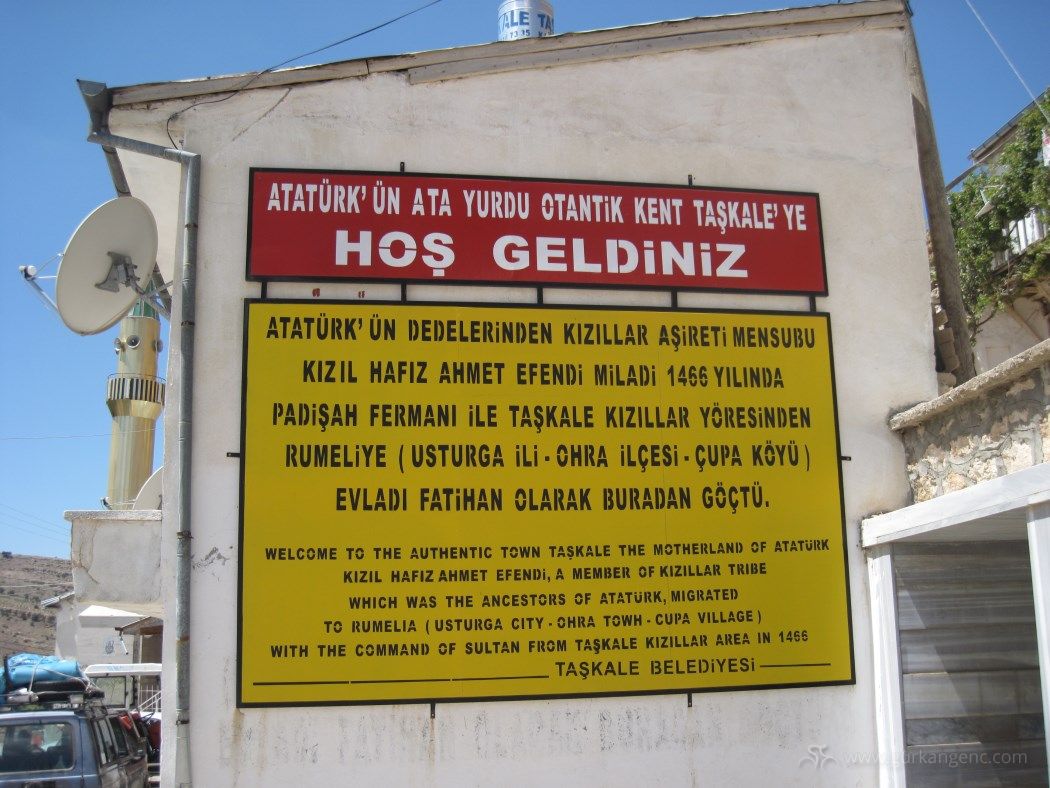

After Kizillaragaini village we arrived in Tashkale. Formerly a town with its own municipality Tashkale has become a district of Karaman with the recent regulations. This arose many problems as students had to attend schools in Karaman about 45 km away from Tashkale. Families with small children migrated to Karaman or Eregli due to educational constraints. There are groceries, bakeries, Turkish cafes and patisseries, but it is hard to find fresh vegetables here as is the case in the neighboring villages.

The historical importance of Tashkale comes from that the ancestors of Ataturk migrated from Balkans were settled by Ottomans in this district. Therefore, Tashkale is also called as fatherland of Ataturk. The wheat storerooms carved in rocks and the stone mosque in the city center is worth to visit.

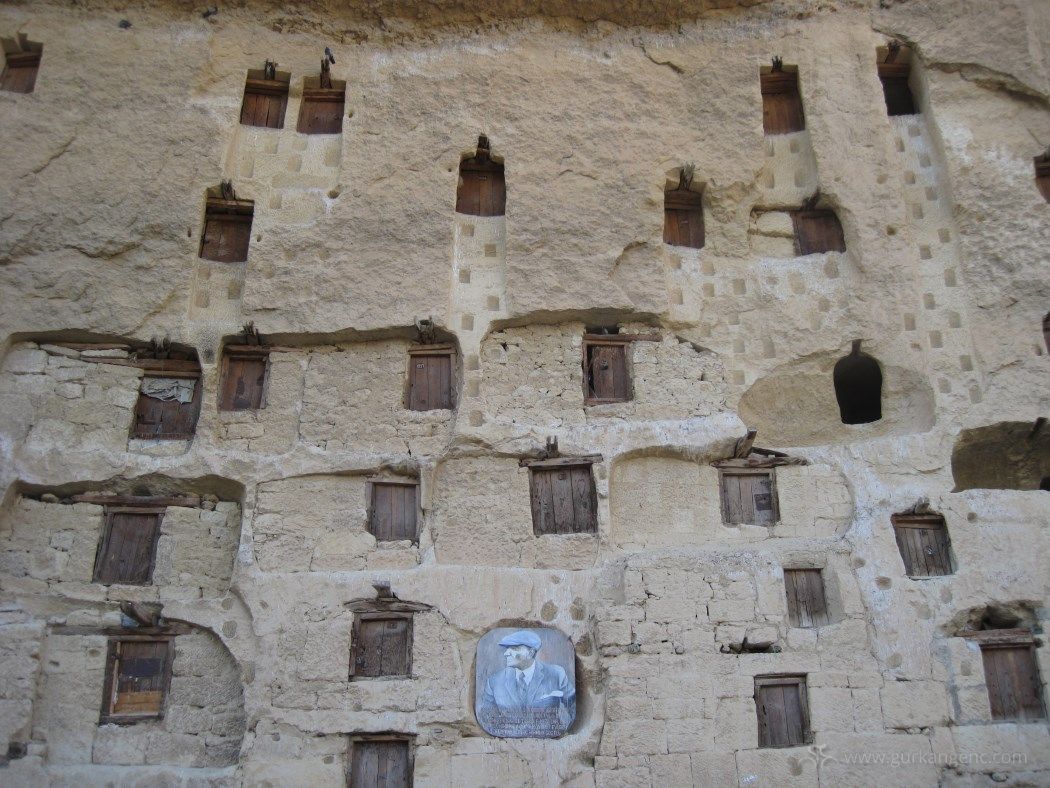

Tashkale wheat storage rooms

There are 251 storage rooms carved into the rock about 40 m high from the ground. The generally two compartmented stone rooms are used to store barley and wheat dating back to the period of Hittites. Barley and wheat are transported to the stone rooms by a pulley system. The stone storage rooms indicate also that this city was established for defense. It is mentioned that during war times women and children used to hide in these caves. Tash cami (stone mosque) still in use was formerly a church of early Christianity.

After Tashkale we rode to Manazan caves 10 km outside the town. On the road, about 500 m before these caves we stopped at a place called priest’s house hard to recognize from the road but an excellent camping site for a small group. A stone staircase leads to a small stone-settlement with spring water.

Manazan Caves

Manazan is a rock settlement having hundreds of carved rooms connected with many tunnels and galleries stretching over five stories across a cliff. Stories are connected with vertical steps carved in to the rock. The city of Manazan dating back to Byzantine Empire features an entire rock face naturally protected from invaders housing churches, storage facilities, family homes and cemeteries. About 100-150 well preserved corpses were found in the necropolis of Manazan. Although most of the tombs had been looted by time, a shirt and some other textiles were recovered during an excavation which is now displayed in the Karaman Museum still upon the body of its owner dating back to 8th century AD.

After visiting the Manazan caves we returned back to Tashkale and from there we rode to Incesu cave. It is about an hour ride from Tashkale but since we had a long day we arrived late in the evening. Finding a suitable place near the cave we immediately put our tents up. Having a soup for dinner we fell asleep. The next day we called the watchman of the cave.

Incesu Cave

This cave is located on the east slope of Incesu stream 9 km to the south of Tashkale. This cave system consists of two interconnected caves. The horizontal cave 1356 m in length bears many stalactite, stalagmite formations and travertine pools. In rainy seasons an underground river from Incesu cave to Asarini cave (750 m) can be followed. This cave was opened to visitors in 2013 with a 1050 m long walk way. Unfortunately this Miocene aged cave was subjected to our vandalism against nature and history. Many of the stalactites and stalagmites were either broken or cut. But still we were impressed by the beauty of the cave. Close to this cave there are remains of a small rock settlement dated back to Roman Empire.

Leaving Incesu cave towards Tashkale there is a branch to the left at the 4.4th km. Riding about 1.2 km on this dirt road it branches to the left where there is a small garden in the corner. Riding about 2 km there is a short cut to the left leading to a fountain with plenty of water. Continuing to ride on this dirt road it branches again, take the right hand side or if you take the left hand side turn to the right when reaching a huge marble block. Make a detour after 1 km taking the small branching road to the left. This road ends at a nomad’s stone house.

Here welcomed us the children of Baycan family; Sude, Sevgi, Sila, Süleyman at the ages of 4, 9, 11 and 13 respectively. The family Baycan stays here in summer time grazing their herd and migrate to their winter dwelling across Manazan caves. In past times many families were migrating with their camels to this place but nowadays only two families were left. The stone house was built using the remains of a church found nearby. At the entrance a stone used as staircase caught our attention on which a carved crucifix was visible. Usually people dwelling near ancient ruins use the stones for building their houses and as garden walls.

Here again we were welcomed by heart. They shared their meal composed of sheep milk, cheese, butter and flat bread with us. We gave candies and chocolate we had bought in the city to the children. Then, we were offered delicious boiled corn. I must say that with such natural nutrition one’s life extends : ). Since we shared our bread with the dogs on the way to Incesu cave we hadn’t left with any bread for breakfast. The women of this nice family baked for us bread enough for a couple of days.

We played with the children and draw some pictures. Sude was the youngest and the cutest among the children. We drew eyes, nose and limps on the face of her rag doll. While chatting we were told that there are remains of an ancient settlement around. We decided to visit this place with the children and get water from the spring for the family. Unfortunately, as is the case in many places in Anatolia these remains were looted by treasure hunters with a great degree of vandalism. Who knows when we realize the value of the historical heritage we live on. Huge stone blocks were scattered all over the place excavated by bulldozer or exploded by dynamite. The historical basin into which the spring water was flowing caught our attention. It was hard to leave but we had to move on. We promised to print their photos and deliver the next time we visit this family which for sure we’ll do.

Our next camping site was Goedet canyon where there are rock settlements at the slopes of the canyon dating back to the same time period of Manazan caves. There is only one large dirt road till Gucler village then after a paved road till Guldere village. After Cimenkuyu village the road branches into three directions. The left branch goes to Mara (Kirobasi) where you can ride down to Erdemli, the second to Guldere and the right branch to Karaman 40 km away. From this branch Guldere village is only 6 km away. From Guldere village it is a 3 km ride to enter the canyon. There is a nice camping site in this narrow canyon with spring water emerging from a rock.

Goedet rock settlements

The rock settlements on slopes, which must have had a function of a fortress also, were used both for religious and daily purposes playing an important role during the period of early Christianity. Manazan, Divle (Ucharman), Goedet (Guldere) and Bugdayli caves are examples of such rock settlements. These many settlements in this region must have played an important role during the initial period of Christianity expansion.

Goedet is located on the road connecting ancient Lycaonia to Cilicia following the route from Laranda (Karaman) to Seleuceia (Silifke) over Fisandon (Derekoy) and Claudiopolis (Mut). The rock settlements at the entrance of the village dating back to early Christianity have been used for housing and storage purposes. There is a preserved small rock church its entrance gate ornamented with a niche north of the village. About 2.5 km to the east at the north slope of the Goedet stream a carved tomb and small chapel (Stone Church as the natives call) is worth to visit. Another rock-cut church around the village is called as Yazili (inscriptive) church. On the south slope of the stream, called by the natives as Yabangulu (wildrose) there is an impressive rock settlement resembling that of Manazan. Besides the multi stories big cave there are smaller caves with 2-3 stories. The carved rooms serving as churches, housing, storage and also tombs are interconnected via galleries. These rock settlements are presently used as storage rooms or for keeping their cattle by the villagers. This narrow canyon has an amazing view from the rock caves. Also within the village Roman and Byzantine periods can be traced back on the walls of the houses.

People of Guldere village are very friendly and hospitable. They rejected to take money from us for vegetables and bread they gave us. We were invited to a wedding ceremony the next day but unfortunately we had to leave. Actually all people we met in small villages were very friendly. The first sentence was always: “Are you thirsty, are you hungry?” They share what they have. We were many times invited to visit again.

The next day, early in the morning, we climbed the slope to visit the rock settlements. Afterwards, rode towards Dag Pazari village.

This dirt road is generally uphill which ends up in paved road.

Dag Pazari (Coropissos)

Dag Pazari village about 35 km north of Mut is an impressive site at 1400 m occupied at least from the 5th century BC. Epigraphic evidence shows that it was a city in the 2nd century AD and a bishopric by the 5th century. The this site identified with Coropissos (Coriopio in the Peutinger Table) is situated on the major route from Laranda (Karaman) to Olba and Claudiopolis (Mut) down to Seleucea (Silifke). The modern village stands on this ancient site, unfortunately construction of new buildings spared none of the ancient buildings. The church at Dag Pazari one of the four famous Isaurian churches is dated to the last quarter of the 5th century to the period of the Emperor Zeno. The remains of the aqueduct, the entrance gate of the city and the church (claimed to built within pagan precincts and from the remains of razed temples) can be visited. This site was mentioned by the British traveler Davis in 1875 and in the studies of Headlam and Ramsay in 1890. The British archeologist Gough excavated this site between 1957-1958 .

In Dag Pazari we visited the aunt of a student of Nuzhet Hoca (Hoca – teacher in Turkish) where we had our lunch and took a shower in the garden with cold water from the garden hose : ).. After having a good rest we set off around 4 p.m. Although steep slopes, we were luckily riding on paved road. Following a mountain route we came to a forested area, the Kestel mountain national park. Our last destination was Alahan monastery the end of our first journey. Riding down the Sertavul pass, a long 10% decline, some of us passed the branch road for about 15 km : ). Gathering at the entrance of Mut we had to return to the branch leading to Alahan monastery a really magnificent place, a must-to-visit. Built on the slope of the mountain it has an impressive panoramic view. It is 2 km from the main road. There is an entrance fee, we used our museum cards.

Alahan Monastery

The monastery of Alahan a place of pilgrimage is located near Mut on the road between Karaman and Silifke. Its foundation is dated to second half of the 5th century AD at an altitude of 1200 m raising over the Calycadnus (Goksu) valley.

The large cave at the western end of the complex had been the first place of worship. Outside this cave there is a basilica (West Basilica) which is connected by a colonnaded walk to a second basilica (Koja Kalessi) at the east end. There are also remains of a baptistery, subsidiary buildings and the cemetery. The monastery reflecting the finest achievement of Isaurian stonemasons and sculptors is in the tentative list of UNESCO World Heritage since 2000.

The article “Alahan monastery – A masterpiece of early Christian architecture” written by Gough is worth to read before visiting this place.

Visiting Alahan monastery at the end of the day we completed our first route what we called “Riding through history”.

Explorers

Nuzhet Türker

Hakan Akıllıoğlu

Hanifi Sarı

Okan Demir

Alperen Sert

Thomas